About Ice Shelves and Icebergs |

|

An ice shelf is defined as a permanent piece of floating ice connected to a landmass. Ice shelves are found along the coasts of the world’s two remaining ice sheets, Antarctica and Greenland. A few well-known shelves dot the northern hemisphere along Canada’s coast, but the majority of ice shelves are found along the coast of Antarctica. Most ice shelves reside along coastlines, which provide protection from warm seawaters and destructive winds. Because of this, ice shelves can survive for thousands of years and grow into massive structures.

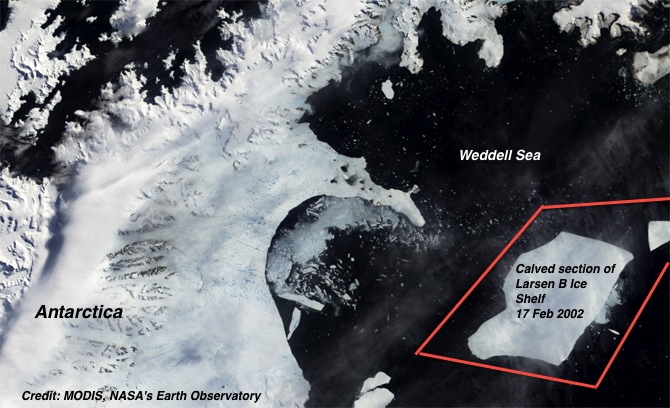

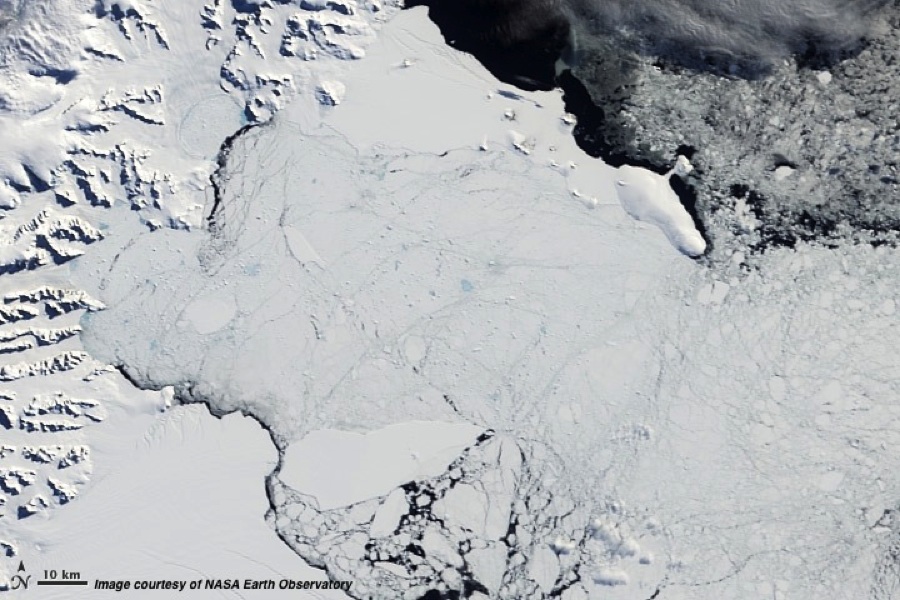

Ice shelves maintain their size and stability by gaining and losing mass periodically. When an iceberg falls off an ice shelf, mass is lost, and the process is called “calving”. Calving is a type of ablation. Ice shelves grow when they gain ice from land, usually from glaciers or ice streams.

Rising global temperatures have already had a noticeable impact on the health of ice shelves and the glaciers that feed them. Ice shelves do not contribute directly to sea level rise because they already float on the ocean surface. However, warmer temperatures take their toll on the waters surrounding shelves, leading to less protection from high winds and warm water. There have been several instances in recent decades of some of the most prominent shelves on earth breaking up, such as the Larsen B ice shelf off the eastern coast of Antarctica in 2002. Once a shelf breaks up or breaks off of the coast, the dynamics that controlled the source (like a glacier) are disrupted. Without the backpressure of the ice shelf to slow movement, the glaciers feeding the shelves accelerate more rapidly, leading to more frequent and larger calving events, and in turn raising the global sea level.

Ice shelves are important components of the ice sheets, and processes leading to their demise need to be well understood. Recent studies have shown that the ice shelf collapse can be very short (seconds-months) or long (decades-centuries) (Shepard et al., 2003), and that occasional observations may not suffice to further our understanding of the phenomenon.

Icebergs form from calving glaciers and ice sheets. Icebergs are found all around Antarctica, and can drift considerably farther north than the sea ice. In the Arctic, large numbers are found around Greenland, throughout Baffin Bay and southward along the east coast of Canada as far as the Gulf Stream; they are found less frequently elsewhere in the Arctic.

Satellite imaging has tremendously improved iceberg monitoring, particularly with the advent of SAR and Side-Looking and Forward Looking Airborne Radar (SLAR/FLAR) sensors that can see through clouds. The size of icebergs range from small “bergy bits” the size of a piano to massive table bergs hundreds of square kilometers in area and tens of meters high above the waterline. Large icebergs like these can significantly affect the oceanographic conditions through fresh water inputs from melting. Smaller icebergs pose significant dangers to navigation. Satellite technologies help identify large bergs, but smaller icebergs are more difficult to detect from space. SLAR/FLAR sensors on aircraft are used operationally to identify bergs from low altitude (1000-3000m).

|

|

References:

Shepherd, A.D. Wingham, T. Payne and P. Skvarca, 2003: Larsen Ice Shelf has progressively thinned. Science, 302, 856-859.

Resources:

What is an iceberg?, by NOAA and the National Ice Center (NIC)